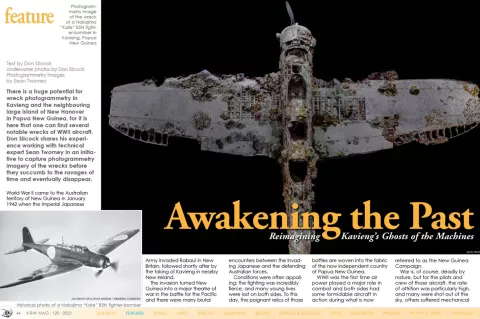

There is a huge potential for wreck photogrammetry in Kavieng and the neighbouring large island of New Hanover in Papua New Guinea, for it is here that one can find several notable wrecks of WWII aircraft. Don Silcock shares his experience working with technical expert Sean Twomey in an initiative to capture photogrammetry imagery of the wrecks before they succumb to the ravages of time and eventually disappear.

Contributed by

Factfile

ABOUT KAVIENG & ITS DIVE SITES

Located just two degrees south of the Equator, Kavieng is often described as a typical “Somerset Maugham South Sea Island port”—which can be loosely translated as “friendly, laid-back and quiet.”

It is both the main town on New Ireland and the provincial capital, plus it has a nice, new airport that is serviced by both Air Niugini and PNG Air, with regular flights from the capital Port Moresby.

THE RESORT

Lissenung Island Dive Resort is located about 30 minutes from Kavieng and is ideally positioned to dive the many excellent sites on both the Pacific Ocean side of New Ireland and those on the Bismarck Sea.

Dietmar Amon discovered many of the dive sites and wrecks, so he knows exactly when they can be dived (not straightforward, with up to six tides per day) and can tell you everything that is known about the wrecks and their histories.

PORT MORESBY

Papua New Guinea’s capital of Port Moresby is the only international gateway into the country and is easily accessible from Brisbane and Cairns in Australia, Singapore and Manila.

World War II came to the Australian territory of New Guinea in January 1942 when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Rabaul in New Britain, followed shortly after by the taking of Kavieng in nearby New Ireland.

The invasion turned New Guinea into a major theatre of war in the battle for the Pacific and there were many brutal encounters between the invading Japanese and the defending Australian forces.

Conditions were often appalling; the fighting was incredibly fierce, and many young lives were lost on both sides. To this day, the poignant relics of those battles are woven into the fabric of the now independent country of Papua New Guinea.

WWII was the first time air power played a major role in combat and both sides had some formidable aircraft in action during what is now referred to as the New Guinea Campaign.

War is, of course, deadly by nature, but for the pilots and crew of those aircraft, the rate of attrition was particularly high, and many were shot out of the sky, others suffered mechanical failures and some just got lost and simply ran out of fuel.

Many of those planes went down in remote jungle locations or far out to sea and have never been found—but some have and each one has a special story.

Kavieng

During WWII, the small town of Kavieng played a very strategic role in the grand Japanese plan to seize all of New Guinea and use it as the launching pad to invade Australia to the south. Located on the northern tip of the long rifle-shaped island of New Ireland, Kavieng was effectively the backdoor to New Guinea and the entry point for supplies coming down from the main Imperial Naval base at Truk Lagoon.

To protect that backdoor, the Japanese established a naval facility, significantly expanded the original Australian-built airfield and set up a sea-plane base—all of which came under heavy attack when the Allied forces launched their counter-offensive in 1944. And so scattered around Kavieng, and its many small islands, are numerous WWII aircraft wrecks—the majority of which are easily accessible and dived.

Most are Japanese, with seemingly strange names like Kate, Pete and Jake. The names had been assigned by the Allies to make identification easier—with men’s names for fighter aircraft, women’s names for bombers and transport planes, bird names for gliders and tree names for trainer aircraft.

Diving the aircraft wrecks

As with all wrecks, the quality of the dive depends on the physical condition of the wreck and the prevailing conditions on the site. With the Kavieng aircraft wrecks, there are three flavours… starting with the ones that came to rest offshore. The best of those is the “Deep Pete”—a Mitsubishi F1M seaplane located on the western side of Nusa Lik (small Nusa) Island, which provides shelter for Kavieng’s harbour.

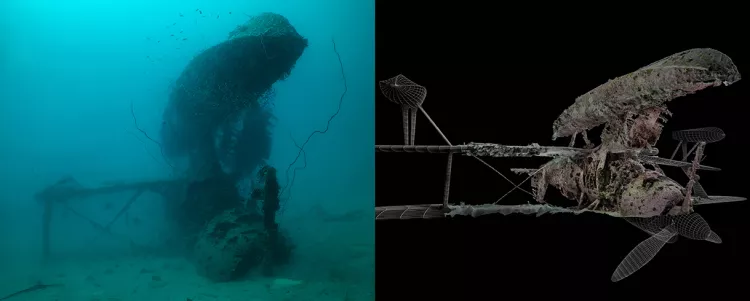

The F1M was a biplane, with a single large central float and stabilising floats at each end of the lower wing. The wreck lies upside-down on flat white sand in 40m of water—hence the “Deep”—and its location on the Pacific Ocean side of Kavieng means that the visibility is often in excess of 30m. What makes the Deep Pete so special is the large resident school of yellow sweetlips that stream around the wings and the batfish and barracuda that patrol above the wreck.

At the other end of the scale are the wrecks in the harbour or close to the mangroves around the islands, where the visibility can be extremely challenging, thus making photography almost a moot point. In-between are those wrecks in which the pilot had tried to bring the plane to rest in the shallows near one of the islands, and usually these are reasonably intact wrecks and interesting dives.

Photographing the aircraft wrecks

I have been fortunate to have dived all the wrecks, and certain ones, like the Deep Pete, several times. I have really enjoyed capturing what they have become and then researching the plane’s history and reputation. Sometimes it is even possible to learn about who the pilot was and, if they survived the crash-landing, or what happened to them after the war—providing a touching vignette back into the turbulent and dangerous times of WWII.

While happy with my images and stories, I always felt limited by the fact that the wreck is what it is… Sure, you can use images from the internet to compare it with what it was, but the wreck is always what it has become after some 80 years underwater.

And then I met Sean…

Reimagining Kavieng’s wrecks

Sean Twomey is an avid Irish technical diver who now lives in Sydney and subscribes strongly to the “Lust for Rust” philosophy of Pete Mesley, the technical expedition leader and wreck expert from New Zealand. His day job is technical support for 3D CAD/design software, so you could say he knows his “ones” from his “zeros” and, if it was not for his wonderfully redeeming Irish heritage and love of a pint or two, he could easily be confused with a “tech-head.”

His software background has led him into the parallel universe of photogrammetry—a word that I could not even spell until I got to know Sean. For the uninitiated, photogrammetry, at its most basic level, involves taking a lot of repetitive, close-range images as an object is traversed. A specialised software is used to compile them into a 3D version of that object, which can be viewed from any perspective, animated and superimposed upon to illustrate its original state.

It is cool stuff and it really impressed me when Sean showed me the results of his first major project on the wreck of a Betty Bomber in Truk Lagoon—over an obligatory pint of Guinness in my local pub in Sydney. Sean had heard about my many trips to Papua New Guinea through a mutual acquaintance and approached me for advice on where to go for the best wrecks.

As soon as I saw the Betty Bomber animation, I thought of the incredible B17F Blackjack bomber wreck on the northern coast of New Guinea. But the wreck’s 50m depth and remote location presented a considerable logistical challenge, so I suggested Kavieng because the variety of aircraft wrecks, the relative ease of diving them, and some wonderful people I knew there made it all a “no-brainer.”

Lissenung Island

Dietmar Amon arrived in Papua New Guinea in 1996, looking for adventure and an escape from the cold weather of his native Austria. He got both in spades when he bought the small island of Lissenung, located about 30 minutes by small boat from Kavieng.

With no water or power on the island, Dietmar spent months sleeping under the stars while building the infrastructure for a dive resort. Joined in 2005 by his wife-to-be Ange, together they have built an excellent operation they proudly describe as the “best little dive resort in the South Pacific.”

I have been to Lissenung several times and had some great adventures in the process. So, I knew how passionate Dietmar and Ange were about the area and its WWII heritage, and I was sure they would be interested in our project.

But this was May 2022, just as the dark clouds of the coronavirus pandemic were lifting, and the couple and their resort were just emerging from two years of almost zero guests, while still helping their staff survive in a country where there was no government-funded assistance.

It was a BIG ASK, but there was no hesitation. “Just get here, and we will make the rest happen” was their response. And so, in November 2022, Sean and I left Sydney for the three-flight journey to Kavieng—Sean’s first trip to Papua New Guinea, and my 24th… Hey, it’s addictive!

The initial project

There is tremendous potential for wreck photogrammetry in Kavieng and the neighbouring large island of New Hanover, but we decided to start with just three wrecks and make a success of them before taking on to bigger challenges.

We began with an intermediate "Goldilocks" wreck (not too deep and not too silted) of a Nakajima Kate B5N fighter-bomber. Sean was responsible for the photogrammetry images and I was responsible for taking the still images, all with the basic objective of complementing our images for the final result.

We then dived the Deep Pete and were able to capture it in all its glory with the sweetlips doing their thing around the wreck in exceptional visibility. We followed this up by trying the polar opposite and diving the “Non-Deep Pete”—another Mitsubishi F1M seaplane located in the rather murky waters of Kavieng’s harbour.

The results

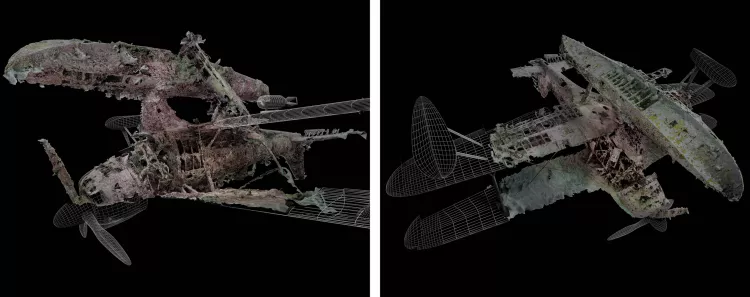

Photogrammetry is a time- and CPU-intensive process that Sean goes about with a quiet but determined concentration that makes all conversation redundant. But what emerged at the end was, for me, staggeringly good, as the level of detail that the processing software compiles is quite amazing and simply not apparent in the 2D still images.

That intense detail is created as the photogrammetry software consolidates all those repetitive, close-range images of the object of interest (the wreck) into what is effectively a layer of high-resolution texture. The texture layer is then wrapped onto the 3D model so that both the geometry and colour definition of the object can be rendered with virtual cameras, which enables an incredible array of options for viewing and orbiting, changing the field of view, animating and lighting the object.

The 3D model is so powerful and interactive that it is often considered as the result of a photogrammetry project. But in reality, it is just the starting point for adding extra dimension to the story-telling process, which can include emphasising details in specific focus areas of the existing wreck and recreating parts of the wreck that were either damaged on impact or have deteriorated over time.

What it all means

Diving and photographing aircraft wrecks is, for me, a special and quite intimate experience, as their small size and the damage they often suffer on impact always makes me really feel for what the pilot and crew might have gone through. Obviously, WWII aircraft wrecks are a diminishing asset, as more are not being made, and their condition can only deteriorate.

For many years after the war, they were left alone—or worse, as in the case of the Non-Deep Pete, which stood vertically with its heavy nose-mounted engine in the sand and was used as a harbour mooring until it fell over!

But the advent of recreational and technical diving has led to a search for more wrecks while advances in digital photography have allowed them to be documented. Photogrammetry, in my opinion, takes that exploration and documentation to the next level, as there is just no other way to capture the detail and condition of these wrecks like it does. In addition, the compiled 3D model is “spatially aware” through the mapping of the reference points, so original design drawings can be used to “virtually repair” impact damage and provide perspectives of what the original aircraft would look like in its watery grave.