Recent scientific efforts have begun to unravel the complexities of shark behaviour, challenging age-old perceptions, and revealing a world of intelligence and sophistication hidden beneath the waves. Ila France Porcher reports.

Contributed by

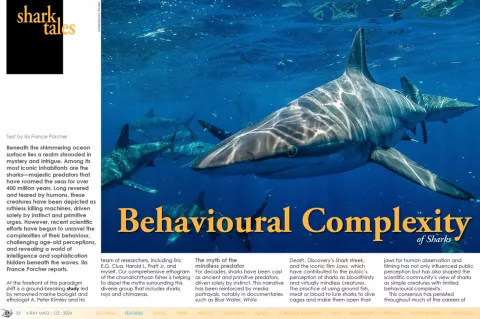

Beneath the shimmering ocean surface lies a realm shrouded in mystery and intrigue. Among its most iconic inhabitants are the sharks—majestic predators that have roamed the seas for over 400 million years. Long revered and feared by humans, these creatures have been depicted as ruthless killing machines, driven solely by instinct and primitive urges. However, recent scientific efforts have begun to unravel the complexities of their behaviour, challenging age-old perceptions, and revealing a world of intelligence and sophistication hidden beneath the waves.

At the forefront of this paradigm shift is a groundbreaking study led by renowned marine biologist and ethologist A. Peter Klimley and his team of researchers, including Eric E.G. Clua, Harold L. Pratt Jr. and myself. Our comprehensive ethogram of the chondrichthyan fishes is helping to dispel the myths surrounding this diverse group that includes sharks, rays and chimaeras.

The myth of the mindless predator

For decades, sharks have been cast as ancient and primitive predators, driven solely by instinct. This narrative has been reinforced by media portrayals, notably in documentaries such as Blue Water, White Death, Discovery’s Shark Week, and the iconic film Jaws, which have contributed to the public’s perception of sharks as bloodthirsty and virtually mindless creatures. The practice of using ground fish, meat or blood to lure sharks to dive cages and make them open their jaws for human observation and filming has not only influenced public perception but has also shaped the scientific community’s view of sharks as simple creatures with limited behavioural complexity.

This consensus has persisted throughout much of the careers of the study’s authors, hindering a deeper understanding of the true nature of sharks. So, the need to challenge this stereotype and demonstrate the diversity of behaviours within the chondrichthyan group was a driving force behind our team’s efforts.

Challenging the fear factor

Due to the widespread belief that sharks were too dangerous for underwater observation, studying sharks in their natural environment was a daunting task for scientists. Klimley was the first researcher to break through this barrier, with his studies of hammerhead sharks schooling around seamounts off California in the 1980s.

To observe the animals in their natural habitat, Klimley dived without scuba gear to depths of 100 to 120ft while videotaping the animals.

He described the experience: “I was a little apprehensive when I first swam over a school of hammerheads, but I took a big breath and propelled myself downward through the school with my long freediving fins. The sharks were only a meter or less to the side of me as I passed them. When underneath the school, I looked up to see the beautiful silhouette of the school above [me] and then powered myself through the school to the surface, where I took a large breath of air. The sharks moved aside as I passed them, but stayed within the school, swimming in a polarized manner.

“In studying the schools, my dives varied around three minutes with the same amount of time at the surface, breathing deeply (called hyperventilating). I wasn’t really scared because scalloped hammerheads have small mouths and feed on fish and squid.”

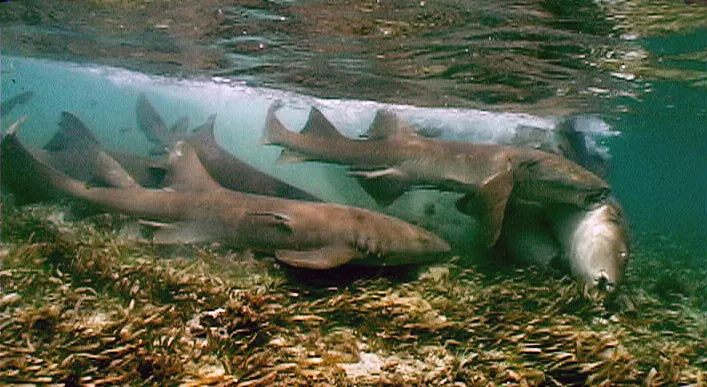

Klimley observed the school members displaying very complex behaviour. The schools were made up of females, which competed with one another to achieve a position at the centre of the schools. The larger females would perform a highly acrobatic behaviour (in diving terms, a “reverse flip with a full twist”), in some instances striking the forward torso of the smaller school members. Just the pulsing light reflecting off the acrobatic female alone could stimulate the smaller females to move to the periphery of the school.

Male hammerhead sharks would dash into the centre of the schools, thrusting their midsections and rotating their sexual organs in a provocative manner, rotating their claspers at the same time, to pair with the dominant females. Once pairing with a female, the two would leave the schools to mate. This entailed the male performing a “love” bite and inserting his male organ, the clasper, into the female’s uterus while sinking down in the water column.

This is just one example of the complex behaviours of sharks. But despite observations such as these, stereotypes persist.

Klimley’s comprehensive review of the chondrichthyan behaviour aims to help shift public and scientific perceptions away from fear and the “simple-minded shark” stereotype, and towards an appreciation of the diverse and complex behaviours that these iconic predators actually display.

The Ethogram: A window into shark behaviour

The ethogram serves as a crucial instrument in understanding the behaviour of wild animals. It comprises a list of behaviours observed in a species or group of species. Each behavioural sequence is named, defined, described in detail, and illustrated.

Konrad Lorenz, a co-founder of ethology and a Nobel laureate in physiology and medicine, emphasised the importance of ethograms as a crucial first step in field studies of animal behaviour. Klimley, as an ethologist in the line of Nikolaas Tinbergen, Lorenz and Arthur A. Myrberg, Jr., carries their legacy forward by creating an ethogram for the entire group of chondrichthyan fishes.

The ethogram constructed by Klimley and his team is divided into eight categories: maintenance, reproduction, filter feeding, scavenging, predation, social, aggressive and defensive behaviours. The meticulous compilation aims to enhance inter-observer reliability by providing a standardised reference and vocabulary for researchers interpreting similar behaviours described for different species. Thus, it will promote a deeper understanding of the complex behavioural repertoire of chondrichthyan fishes. The ethogram’s construction for the entire taxon of chondrichthyes, encompassing sharks, rays and chimaeras, represents a monumental step forward in understanding their collective behavioural complexity.

The ancient lineage of chondrichthyans

To understand the evolution of shark behaviour, it is essential to delve into the extensive ancestral lineage of chondrichthyans, which stretches back over 400 million years to the Ordovician period. The movements of the Earth’s crust during the Permian and Triassic periods, about 200 million years ago, coincided with a significant diversification of cartilaginous fishes. The fragmentation of the single continent of Pangea into Gondwana and Laurasia created new habitats and environmental conditions that led to the evolutionary radiation of sharks into estuaries, bays, the continental shelf and the open ocean.

However, not all early sharks survived the harsh conditions at the end of the Permian. The evolutionary tree of chondrichthyans illustrates a constriction, with ctenacanths likely giving rise to modern sharks or Euselachi. During the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras, chondrichthyans diversified into 13 orders, including chimaeras, sharks and rays.

The study introduces phylogenetic trees showing the relationships among modern sharks and rays based on both molecular and anatomical similarities. It unveils the intricate connections between different orders and provides insights into the evolutionary divergence of chondrichthyans. Evolutionary trees based on molecular and anatomical similarities, combined with fossil evidence, contribute to this understanding.

Brainpower beyond the depths

One indicator of intelligence in chondrichthyan fishes is the brain-to-body mass ratio, which is comparable to that of birds and some mammals. But because they move through a vibrating realm in which light travels less easily than sound, their brains are adapted to perceive their surroundings using specialised senses, particularly the lateral line sense, which directly perceives underwater vibrations.

Because salt water is a conductor, their large cerebellum also plays a crucial role in processing nerve impulses from their electroreceptors. Furthermore, they can also find their way in visually opaque environments by perceiving the local patterns of magnetic fields associated with the seafloor and its contours. The brain-to-body mass in cartilaginous fish is also indicative of cognition (the term used for thinking in animals), which is suggested by many of their actions.

The study postulates that the more derived sharks and rays in the chondrichthyan lineage have evolved the most diversity and complexity in their behavioural patterns, as reflected in their actions and in their larger brain-to-body ratios. The study’s inclusion of a wide range of behaviours, including some of those observed in captivity, contributes to a holistic understanding of chondrichthyan behavioural diversity.

Ethograms for elasmobranchs

Most ethograms published for elasmobranchs in the past have been partial ones, focusing on specific behaviours within a particular study. It is a challenge to publish more comprehensive ethograms due to their length, so they are excluded from journals with limited space.

However, there are journals, such as Behaviour, that are willing to devote the space necessary to publish comprehensive ethograms. Therefore, this ethogram was published as the flagship paper in the recent special issue of Behaviour, “Elasmobranch cognition and behaviour.”

Challenges and future avenues

Despite the groundbreaking insights provided by the ethogram, challenges persist in the study of certain chondrichthyan species. Chimaeras residing in cold temperate and subpolar waters, as well as deep-sea sharks, elude direct observation due to inhospitable environments. The study advocates for more comprehensive research in both natural and controlled environments, emphasising the importance of expanding our understanding of these elusive species.

The ethogram review offers a transformative perspective on sharks and their relatives, challenging ingrained myths and unravelling layers of behavioural complexity. From the ancient depths of the oceans to the intricate details of evolutionary trees, the study invites us to appreciate chondrichthyans as intelligent, adaptive creatures, reshaping our understanding of the fascinating world beneath the waves. ■

Download the study here >>>