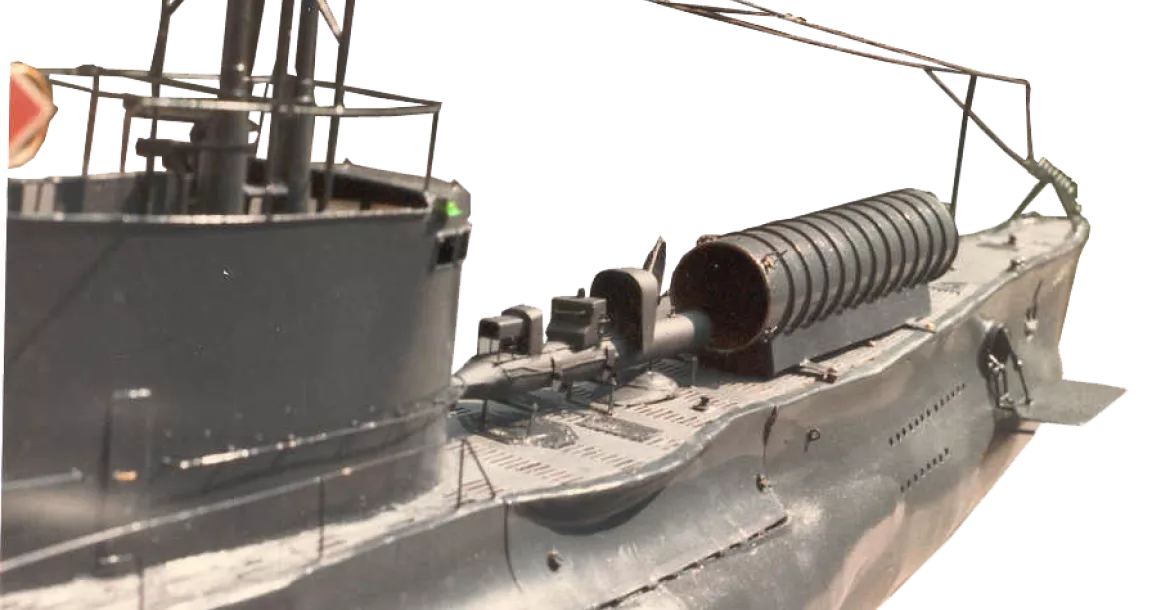

In the years prior to World War II, the Italian fleet had developed a new underwater weapon, the SLC, a slow torpedo which was manned by two divers. Submerged, and thereby unseen, the frogmen on the SLC could get close in to the enemy ships and mine them. The frogmen trained in attacking their own ships, and after many excercises developed a procedure for approach and placing mines under the ships.

Contributed by

Factfile

Literature and sources:

Valerio Borghese, J - Sea Devils, Chicago 1954

Schofield, William and Carisella, P.J. - Frogmen First Battles, Boston 1987

Spertini, Marco and Bagnasco, Ermino - I Mezzi D’assalto Delle X Flottiglia MAS 1940-1945, Genova 1991. Kemp, Paul - Underwater Warriors, London 1996

As soon as the submarine was in position, and the frogmen were out, the containers were opened and the SLC drawn out. The frogmen then tested all the functions of the SLC before setting out for the target. The first part of the trip took place on the surface, when only the heads of the frogmen were above the surface. The frogmen had full face masks on but breathed through a valve in the mouthpiece out to the air in order not to deplete the oxygen stores.

The harbours were generally barred by submarine nets which the frogmen had to pass either under or over. They could also cut their way through using wire-cutters. Free from the nets and into the harbour, the frogmen picked out the chosen target by its silhouette because the attacks took place at night. They had to get so close to the target that they could often hear and see the watch crew on the deck.

During the last part of the trip on the surface the sternmost frogman lowered his head beneath the surface and breathed using his oxygen apparatus, so that there was as little as possible to be seen by any watchmen on the ships. The leading frogman then also went over to breathing using his oxygen apparatus and was ready to release the air from the tank of the SLC. In that way could they quickly disappear from the surface if it happened, for example, that a searchlight could get close and illuminate them.

Acquiring the target

When the target had been identified, and at a distance of ca 30 meters from it, the leading frogman took a compass bearing and then let the SLC disappear beneath the surface. At about 8 to 10 meters depth the SLC was trimmed to sail horizontally. It was now cold, dark and quiet around the frogmen. As they slowly sailed towards the target the frogmen kept an eye on the remaining light filtering down from the surface.

When the light disappeared they knew that they were beneath the ship. The SLC was stopped and a little air was released into the tank between the frogmen so that the SLC now had a slight positive buoyancy causing it to rise up to the bottom of the ship. The frogmen raised a hand over their heads to take the force of contact with the ship’s bottom.

With one hand one the bottom of the ship they returned in the direction from which they had come until the stern-most frogman felt the bilge keel. The bilge keel is a thick piece of sheet-iron which runs along both sides of the hull in order to stabilise the ship against rolling. With a clap on the shoulder of the driver the stern-most frogman told the driver that he had found the bilge keel. He quickly took a clamp and a steel wire from the toolbox behind him and fixed the wire to the bilge keel using the clamp.

Two claps on the shoulder of the driver informed him that the wire was now fixed in place, and the SLC was now sailed over to the other side of the hull where the procedure was repeated. There was now a wire stretched out beneath the ship. Holding the wire the frogmen now pulled themselves to under the middle of the ship. The stern-most frogman now left his seat and crept past the driver in order to fix the mine, which formed the bows of the SLC, to the wire. At the same time the driver of the SLC held it fast between his legs.

After the mine had been fixed the timing mechanism was activated. This would cause the mine to explode 2½ hours later. He then released the SLC from the mine and crept back to his seat. Three claps on the shoulder of the driver told him that the task was completed, and that it was now time to get away. It was impossible to find a way back to the submarine and the frogmen, if possible, had to try and reach a neutral coast where they could sink the SLC. This procedure shown to be possible during training but was found to be much more difficult during operations against the Allies.

Attacking the British

On the 10th June, 1940 Italy declared war against England and France. It was now that the SLC could show what it could do. The first attack was planned for the night between the 25th and 26th August, 1940. The target was the English fleet in Alexandria. The submarine Iride took the frogmen from La Spezia to Bomba west of Tobruk, where Iride met the torpedoboat Calipso, which carried four SLC. This method of transporting the SLC was chosen in order to avoid damage to them should the submarine be forced into deep water.

On the morning of the 21st August, when the SLC were being transferred to Iride, and the submarine refuelled - ready to carry out a test dive – three English torpedo planes appeared on the horizon. They flew low over the sea and opened fire against Iride. A torpedo hit the submarine amidships and it immediately sank in 15 meters of water.

Rescue

Calipso immediately sailed to where Iride had sunk. They found that the frogmen and some of the crew had escaped from the wreck. Without oxygen equipment – it was in the Iride - the frogmen dived down to the submarine and connected a buoy to it. A message was sent to Tobruk asking for help, and after some time a diver arrived with some diving equipment. The frogmen and the diver made contact with the survivors in the submarine using knocking signal. The crew of the submarine signalled that the external hatch of the sluice could not be opened from inside.

The hatch was stuck tightly in the hatch frame by the explosion. However, the frogmen and the diver succeeded in opening the hatch but it was damaged and could not be closed tightly. The frogmen signalled to the crew of the submarine that they should open the second hatch into the hull and attempt to reach the surface. The order was discussed in the submarine but they thought that the crew preferred to remain in the submarine. It was signalled from outside to the trapped crew that they should come out within half an hour or they would be left to their fate. There was no answer.

From the deck of the Calipso the frogmen maintained a watch on the sea and hoped that the crew in the submarine would take a chance rather than await the inevitable. After some time a large amount of air was released from the submarine – the hatch had been opened – and the survivors appeared one by one on the surface after being trapped for 24 hours on the bottom of the sea.

”Enemy ship 800 meters”

The next attempt was made in September 1940. The Italians would attack two English fleet-bases simultaneously – Alexandria and Gibraltar. The submarine Gondar sailed for Alexandria and Scire for Gibraltar. After 9 days at sea the Gondar reached Alexandria on 29th September. At the time intended for the operations to start Gondar received a radio message from Rome: ”The English fleet has left harbour – return to Tobruk”.

The disappointment was great, so close and so had the fleet left harbour. They were very close to the naval-base and probably a watch at the base had observed the submarine and raised the alarm. After just a few minutes sailing the alarm sounded on the submarine: ”Enemy ship 800 meters”. Gondar dived immediately, and a hunt now began during which Gondar was under constant bombardment by depth-charges, causing it to dive deeper and deeper.

The hunt continued all night, and in the morning at 8 o’clock the Gondar could not take it any more and began to sink uncontrollably. All the air was blown into the tanks in order to stop the dive. It succeeded, and the Gondar stopped at 155 meters, but now an uncontrolled rise to the surface began with an ever increasing speed. The crew got ready to abandon the submarine as soon as it had reached the surface. Gondar floated on the surface for only a few minutes before it again sank. In spite of this, all the crew excepting one managed to escape from the wreck. The attacking destroyer collected up the surviving frogmen and submarine crew, among them Toschi who spent the rest of the war as a prisoner.

Attack on Gibraltar

Scire reached Gibraltar at the same time as Gondar reached Alexandria. Just 50 miles from Gibraltar and 4 hours prior to the planned attack Scire received a radio message: ”The fleet has left harbour – return to La Maddalena”. This time was not a success either. The English had apparently detected one of the submarines but didn’t know its intentions.

They were ready for yet another attack on Gibraltar in October 1940. Under the command of Valerio Borghese the Scire would transport three SLC to Gibraltar, where they would attack the English battleships. The frogmen were the same as were recalled from the previous mission. This time the frogmen were with the Scire the whole way from La Spezia to Gibraltar. The Scire reached the Straits of Gibraltar on the 27th October. Two days later the Scire, submerged and against the strong current, succeeded in entering the Strait.

Outside the Bay of Algiceras, where the fleetbase was situated, the Scire waited 70 meters down on the rocky bottom to await the coming night. Sounds could clearly be heard in the submarine from the shipping traffic. In the evening the Scire sailed slowly into the bay. Only the most absolutely necessary equipment was in operation, and the crew avoided any unnecessary noise in order not to be detected. They constantly heard the noise from the screws of the patrol boats passing over them.

Around midnight they were in position 3 miles from the fleet-base, and the submarine rose to the surface in order to launch the frogmen. Here they received the latest messages which stated that there were two battleships in the harbour. All was now ready, and after a short time on the surface the Scire dived again and crept out of the bay. The frogmen were now on their own. After they had completed their operation they should aim for the Spanish coast where an Italian agent awaited them and who would ensure their transport back to Italy.

Equipment breakdown

The SLC of De La Penne and Bianchi was the first to fail. After sailing for about 20 minutes De La Penne dived to avoid a searchlight. At a depth of 15 meters the engine stopped and the SLC dropped to the bottom at 40 meters. It proved impossible to restart the motor, so the frogmen swam to the surface, got rid of their oxygen equipment and began swimming towards the Spanish coast.

Tesei and Pedretti got right in to the north mole of the naval base, only to discover that one of the oxygen apparatuses was filled with water and the other had other malfunctions. The reserve apparatus also proved to be unusable. Furthermore, it was not possible to trim the SLC which was sloping downwards towards the stern. The frogmen decided to call off the operation. They dropped the explosive charge and sailed off towards the Spanish coast.

Attack on HMS Barham

Birindelli and Paccagnini also had problems in trimming the SLC. One of the oxygen apparatuses was filled with water but was substituted by the reserve. Soon after there were problems with the motor, which could only function at low revolutions. The SLC became heavier and heavier, probably because water was getting in. In spite of this, they managed to continue with the bows above the water, keeping the SLC floating.

But the SLC was so inclined in the water that the sternmost frogman was beneath the surface and had to use his oxygen apparatus. In the entrance to the harbour they had to be on the surface and get past some floating barriers densely covered with iron spikes. After passing the second barrier they found the battleship Barham just 250 meters in front of them. They took at compass bearing on the battleship and let the SLC sink to the bottom 14 meters below.

However, the oxygen in the sternmost frogman’s apparatus was now exhausted and he had to rise to the surface. Birindelli continued along the sea bottom but the motor soon gave up. Birindelli ascended to the surface and found that he was just about 70 meters from the Barham. He immediately let himself sink to the bottom and attempted to manoeuvre the SLC under the battleship. After half an hour’s hard work he was totally exhausted and his oxygen used up.

He activated the fuse and ascended to the surface. He got rid of his apparatus and suit, and climed up on to the mole where he managed for a short while to keep himself hidden.. However, he was discovered and handed over to the English. Shortly afterwards the charge exploded without damaging the Barham. The rest of the frogmen reached Spain and returned from there to Italy, but Birindelli and Paccagnini were held as prisoners for the rest of the war. ....

10th flottila

No more attempts were made with the SLC that year, and on the 15th March 1941 the 1st Light flotilla, to which the frogmen belonged, was reorganised and given the cover-name Decima Flottiglia MAS (10th Light Flotilla).

The long submarine trip was not good for the physical condition of the frogmen during the operations, and so another solution was found. In Cadiz on the coast of Spain, only 70 sea miles from Gibraltar, lay the interned Italian freighter Falcon. The frogmen were flown from Italy to Spain and billeted on the Falcon. Under cover of the night the Scire fetched the frogmen from the Falcon.

On the 25th May 1941, Valerio Borghese again sailed the Scire into the Bay of Algeciras and launched three SLCs. One of the SLC was sunk immediately, as the motor would not start. The two other SLCs now continued with three frogmen on each, but both sank close to their targets. All six frogmen reached the Spanish coast and returned to Italy. During the operation the harbour area was constantly bombarded with depth charges from patrol boats - the English had taken their precautions.

Heavy losses

Simultaneously with the underwater operations a number of surface operations with the MTM-boats were also carried out. Two SLCs took part in one of these operations, the attack against Valletta Harbour on Malta the 26th July, 1941. During this attack, which ended in a fiasco, Tesei and Pedretti were killed when they probably suicidally used their SLC to break through a steel net that was barring the way for the attack of the MTM-boats on the harbour. Among the many victims of the operations was also Moccagatta – the head of Decima Mas. His position as chief was temporarily filled by Valerio Borghese.

The many fiascos didn’t discourage the Italians. The operations had revealed faults in the SLCs and under the leadership of Valerio Borghese the SLC underwent several modifications. The new SLCs were, however, not ready for the next operation that against Gibraltar.

After fetching the frogmen in Cadiz, Valerio Borghese again sailed the Scire into Gibraltar. Just after midnight on 20th September, 1941, the Scire surfaced and launched three SLC. They had been informed from Rome that, among others, there was a battleship and an aircraft carrier in the harbour. Vesco and Zozzolli should attack the battleship which was anchored in the harbour itself, but had to give up entering the harbour.

Several times during the passage they noticed pressure-waves from depth-charges that were being dropped for their sakes. So, instead they chose another target, a freighter. The mine was suspended, and after the charge had been activated the SLC was sunk. The frogmen swam to the Spanish coast from where they could see the explosion which ripped the 2440 ton English tanker Fiona Shell into two halves.

Catalano and Giannoni were pursued by a patrol-ship and had to hide on the bottom. When the danger had finally gone the time to enter the harbour had passed, and they suspended the mine instead under a freighter. After sinking the SLC they, too, swam to the coast and from here experienced the violent explosion. The ship began to sink at the stern, but four tugs arrived and towed it aground. The ship was the armoured freighter Durham of 10,900 tons.

Visintini and Magro also had to dive to avoid being detected by a patrol boat. They moved towards the entrance to the harbour and passed three strong steel-wires which were probably part of the barrier to the entrance. In spite of the constant explosions from the depth-charges at the barrier they got into the harbour where they saw a light-cruiser and four large tankers. As the cruiser lay close to the harbour entrance they gave up this as a target because of the depth-charges.

nstead, they attacked one of the tankers and hoped that the consequent discharge of oil would set some of the harbour on fire. They placed the bomb under the fleet-tanker Denby Dale of 15,893 tons. From the Spanish coast they heard first a large explosion and thereafter four to five small ones. In addition to the Denby Dale, a smaller tanker, which was moored to the side of the Denby Dale, sank.

The SLCs had at last proved their worth, but Tesei had been killed and Toschi taken prisoner.

It was round about this time that Decima Mas began to train free-swimming frogmen who, in tight-fitting black rubber suits, with blackened faces behind their masks, and wearing fins on their feet, would swim in to the enemy ships and mine them. They decided on this because they saw that sinking a cargo ship with 300 kg of explosive was equivalent to using a sledge-hammer to crack a nut. A program for training gammamen was established. The best swimmers were chosen from all units and given a hard training. The gammamen would later prove their worth.

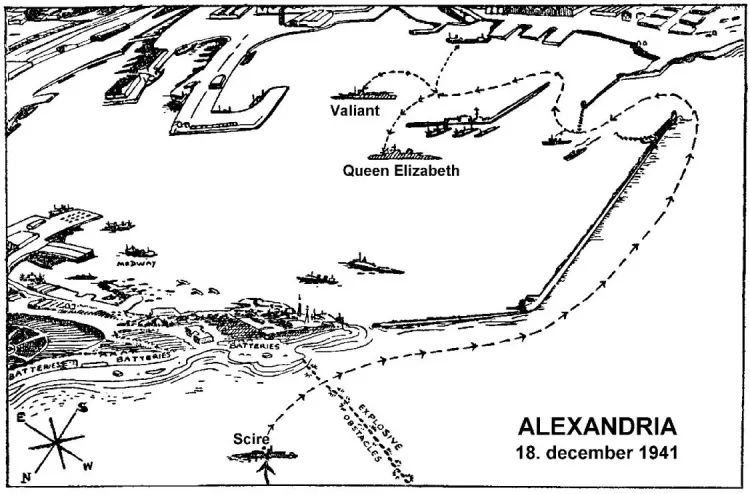

18. December 1941

The Italians were now ready for another attempt to get into the English naval base at Alexandria. The attack was carefully planned and once again it was Scire that would transport the frogmen.

The English now knew about the frogmen and had reinforced the defences of the base. As in the case with Gibraltar, depth-charges were constantly dropped at the barriers and in the harbour. On the 18th of December, 1941, Scire lay on the bottom outside Alexandria after having fetched the frogmen on the Greek island of Leros, and after having passed through a minefield outside the harbour.

The frogmen dressed themselves in rubber suits and oxygen equipment, and just before midnight Valerio Borghese took the Scire to the surface.

The containers were quickly opened, the SLC pulled out, and the Scire dived again. In the Scire’s hydrophones the crew could hear that everyone was on the way to Alexandria. The night was dark and the sea calm, and about 500 meters from the mole the frogmen could see and hear people on the mole.

Just as they came to the net which barred the entrance to the harbour it was opened to permit the passage of three English destroyers. The frogmen were quick, increased their speed and slipped into the harbour together with the destroyers.

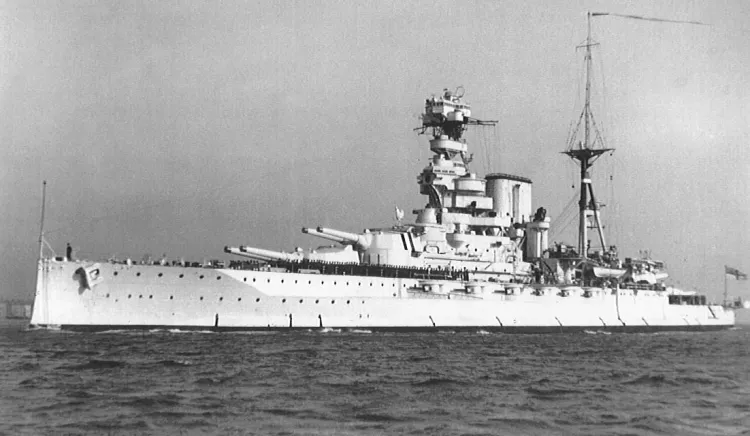

Valiant

De La Penne and Bianchi should attack the 32,000 ton English battleship Valiant. The battleship was an enormous shadow in front of them. About 30 meters from the Valiant they sailed into a torpedo net, which caused the SLC to list.

De La Penne was feeling the cold dreadfully, his suit was leaking and he was soaked through. Unseen, they sailed towards the battleship and right up against the side of the ship they let the SLC sink to the bottom. However, the SLC sank uncontrollably and left De La Penne on the surface. De La Penne dived to the bottom 17 meters down and found the SLC. He discovered that Bianchi was gone. He attempted to start the SLC but had to give up when a wire became tangled in the screw.

The hard work now began of pulling the SLC in under the middle of the battleship. De La Penne could hear noise from the ship above him, and expected at any moment to be depth-charged when the English caught sight of Bianchi who must be on the surface some where or other.

After about half an hour’s work he banged his head against the bottom of the ship. He was exhausted and thought that the SLC was now well positioned. The charge was activated and he swam to the surface.

Here he tore off his mask and enjoyed the fresh air. De La Penne swam immediately to a nearby buoy and found that Bianchi had had the same idea. Before he reached the buoy, however, he was caught in the beam from a search-light. A salvo from a machine-gun made him stop, and shortly afterwards both frogmen were taken up by a motorboat and brought to the Valiant.

The English were quite clear about what the frogmen had been doing, and demanded to know where the charge had been placed - they received no answer. The frogmen were taken to land, and in the meantime a steel wire was dragged along the bottom of the Valiant, but to no avail because the mine lay on the sea bottom.

On land it had proved impossible to get anything out of the frogmen, so it was decided to sail them back again to the Valiant, where they were interrogated by Captain Morgan. The result was the same. In an attempt to make them change their minds they were locked in a cabin below the water-line.

“All men on deck”

De La Penne had kept his waterproof watch on, and as there was now 10 minutes to the explosion, he asked to speak to the Captain. He explained to Captain Morgan that the ship would be blown up in a few minutes and recommended that all men be sent on deck. As Morgan could obtain no information about where the mine was placed De La Penne was again locked in beneath the waterline.

From his ‘cell’ De La Penne could hear the alarm and the command: ”All men on deck”. The explosion was violent, De La Penne was knocked off his feet, the light went out, the cell became filled with smoke, and the ship began to heel to port. He succeeded in finding a way out and got to the deck, where he met Bianchi and Captain Morgan. From the deck he could keep an eye on the other battleship, the Queen Elizabeth, which

Marceglia and Schergat had intended to attack. The ship lay some 500 meters away, and he could clearly see the crew on deck. Suddenly the sea rose up around the Queen Elizabeth. Shrapnel and oil rained down over the Valiant. Marceglia and Schergat had suspended their mine directly beneath the middle of the ship. An English officer wanted to know if there were more mines under the ship – and received no answer.

Succes at last

Shortly afterwards, the harbour was shaken by yet another explosion; it was a 10,000 ton tanker that, together with a smaller tanker laying beside it, was sent to the bottom. Martellotta and Marinos’ attack had also succeeded. The last four frogmen made for the land where, one after the other, they were discovered and arrested. They spent the rest of the war in captivity. The attack had been the success that the Italians had been longing for – two battleships and two tankers sunk without loss of Italian life.

The submarine Ambra later carried out yet another attack against Alexandria with three SLCs. However, the operation failed, and all the frogmen spent the rest of the war as prisoners.

Across bay of Algeciras

At the same time, the attacks against the allied ships in Gibraltar continued. Transport of the frogmen into the target area by submarine became more and more risky as the English increased their armaments in the Mediterranean. The Italians devised a plan.

This plan concerned Antonio Ramognino, who was an officer in Decima Mas and married to the Spanish girl Signora Conchita. Claiming that Signora Conchita’s poor health required fresh sea air, the pair rented a house, Villa Carmela, in the Bay of Algeciras.

From Villa Carmela there was a good view of all the allied ships anchored in the bay, and a swim of only 500 – 2,000 meters to them. For the first operation twelve gammamen were smuggled by different routes into Spain in July, 1942. On the night between the 13th and 14th July, 1942, all the gammamen were gathered together in Villa Carmela.

Here they put on their suits and were equipped with oxygen apparatuses and the mines which they would fasten to the ships. Hidden by the darkness, and without being discovered by English spies, of which there were many in the area, they crept down to the coast and swam individually out to the ships. At a safe distance from the targets they utilised their oxygen equipment, and disappeared from the surface to swim in under the ships and here fix the mines.

Two of the frogmen found their way back to Villa Carmela. Seven were discovered and arrested by the Spanish police when they reached the coast. The remaining three reached the coast in different places without being discovered. The arrested frogmen were, however, soon released on certain conditions agreed between the Spanish and Italian authorities.

However, they didn’t get off completely scotfree. One of them was hit in the foot by the screw of an English patrol boat, and another was injured by a depth-charge that exploded close to him. Even though all the mines had been placed on the targets the damage to the ships was limited. Several of the mines did not explode, and those that did explode didn’t cause more damage than the English could manage to ground the ships. Four ships of in all 9,500 tons were damaged and grounded.

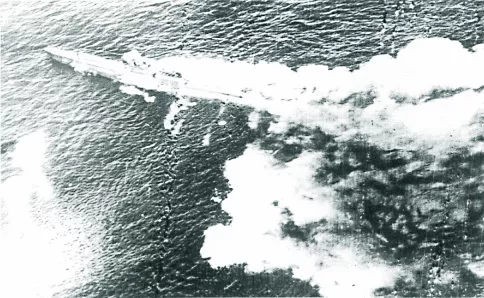

In August 1942, it was intended that the submarine Scire, which had successfully carried out several operations with the SLC, should transport eight gammamen to Haifa, where they would swim into the harbour and place mines under allied ships. The operation ended in a catastrophe for the Scire and all its crew. On the 10th August 1942, the submarine was detected outside Haifa and sunk by the English torpedo boat Islay.

The trojan horse

Immediately across from the English naval base lay Algeciras, where the Italian freighter Olterra lay moored to the mole. At the outbreak of the war the ship had been sunk in shallow water by its Italian crew.

A Spanish salvaging company had later raised the ship, and it was now laying inside the mole with a strong list and several water-filled compartments. Aboard the Olterra were Spanish guards together with a maintenance crew from the owners of the ship who, as far as possible, maintained the ship. Decima Mas saw several possibilities in the wreck, and a plan for its utilisation as a base began to take shape.

Lieutenant Licio Visintini from Decima Mas was chosen to carry out the plan. Visintini hand-picked technicians and seamen from Decima Mas, and arranged for them to replace the maintenance personnel aboard the Olterra. Under Visintini’s direction the Olterra was now secretly rebuilt to function as an observation post, and to house the gammamen and the SLC.

Workshops were established for servicing the SLCs and re-charging of the batteries. A hatch was built under the waterline in the side of the ship, into one of the flooded compartments. The gammamen and the SLC could now leave the Olterra through this hatch, and at the end of an operation could return again unseen.

While these preparations were being made the gammamen continued their attacks from Villa Carmela.

The gammamen and SLC frogmen arrived in Algeciras under the guise of being seamen , and several completely split-up SLCs were transported by car from La Spezia to Algeciras. The first operation from Olterra was carried out on 14th September,1942, by three gammamen, who swam out from the Olterra at 23:30.

One of them was carried away by the current and had to land on, what was for him, an unknown coast, where he was arrested by the Spanish police. He was later returned to Villa Carmela. The two others returned to the Olterra after accidentally mining the same ship. This ship was the 1.787 ton Ravens Point. It sank at its moorings on the morning of 15th September.

The SLCs which had arrived from Italy were re-assembled and tested in the Olterra. Three of these were used in an attack on the 7th December, 1942. On one of the SLCs the frogmen ran out of oxygen in an attempt to avoid patrol boats and depth-charges. They decided to break off the operation and return to the Olterra, but when the SLC reached the Olterra there was only one frogman aboard it. The one at the stern had been lost.

The second SLC penetrated right in to the mole but was detected and shot at. Although rather dazed by the depth-charges, the frogmen succeeded in sinking the SLC and crawling aboard an American merchant ship. They were interrogated but didn’t give away Olterra’s secret. The third SLC made its way through the barriers and into the harbour but was detected and shot at. Both frogmen died.

Several more, and more successful, operations followed from the Olterra. Among them was a successful attempt on 8th May, 1943, by three SLCs, to sink three ships of, in all, 19.000 tons, and return safely to the Olterra.

English minedivers

Under leadership of the English Lieutenant Lionel ”Buster” Crabbe the English had established an ”Underwater Working Party”, who, equipped with Davis-vests, examined the ships for mines. The team succeeded in finding and removing several mines. The English knew what was going on but not where the frogmen were coming from. It was first after the capitulation of Italy on 8th September, 1943, when the English examined the Olterra, that the secret was exposed.

In December 1942 a combined operation with gammamen and SLC was carried out against Allied shipping outside Algiers. The submarine Ambra departed with three SLC and ten gammamen. On the 10th December 1942 the Ambra lay on the bottom outside Algiers. In this operation a frogman was released, via a sluice, from the submarine with a lifeline and telephone cable in order to direct the submarine to the right position.

After the submarine had been manoeuvered into place the frogman was again taken aboard through the sluice. The idea was that after the operation this observer should lead the frogmen back to the Ambra. The observer heard the frogmen but could not see them, and the Ambra had to leave the area at dawn without them.

The frogmen swam into the coast where all sixteen were arrested. From 5 o’clock until 7 o’clock the following morning the harbour echoed to several explosions. And when the day was over two ships of a total of 8,667 tons lay on the bottom, and two ships of a total of 11,628 tons were badly damaged..

Turkey

Also in the Turkish harbour of Alexandretta the English ships, which were to carry chromium ore to England, were attacked by the gammamen. Luigi Farraro, a very good swimmer, was chosen for the operation. Farraro was equipped with diplomatic papers and four very heavy cases. Farraro arrived in the middle of June and introduced himself to the collective diplomatic corps in Alexandretta.

On the evening of the 30th June 1943 he went down to the beach, crawled into the suit, put on the oxygen apparatus, tied two limpet mines to his belt and swam out to 7 000 tons freighter Orion, which lay in the basin. He fixed the mines to the ship and swam unseen back to land. The mines were of that type which were first armed and exploded after the ship had reached a certain speed and sailed a given distance.

On the 9th July and the 1st August the ships Kaituna and Fernplant, of 4917 and 7000 tons respectively, were mined. Orion and Fernplant were sunk in open water, without any suspicion of a frogman attack. Regarding Kaituna, only one mine exploded, and the ship was run aground on Cyprus. During examination by divers the second mine was discovered.

The attacks continued until the final collapse on the 8th September 1943, when the Italian forces surrendered to the Allies or went north to join Mussolini. Together with English frogmen some of the Italian frogmen who surrendered to the Allies carried out underwater operations against the German forces. By that time the frogmen had sunk allied shipping to a total of some 200 000 tons, and they had fully proven the effectivity of the new weapon. Inspired by the Italian frogmen, the English had already established corresponding units in 1942 and built ”Chariots” modelled on the Italian SLC. After the war many nations supplemented their armed forces with frogmen units.

In 1944, after De La Penne and the other frogmen had been released from captivity and sent back to Italy, De La Penne and Bianchi were decorated with a gold medal for courage under the attack on the Valiant. The man that pinned the medals to their breasts was none other than Captain Morgan who they had met a couple of years previously. He was now an Admiral and head of the Allied Naval Forces in Italy.

Post Sciptum: In memory of Dr. Luigi Ferraro

Post Sciptum: In memory of Dr. Luigi Ferraro

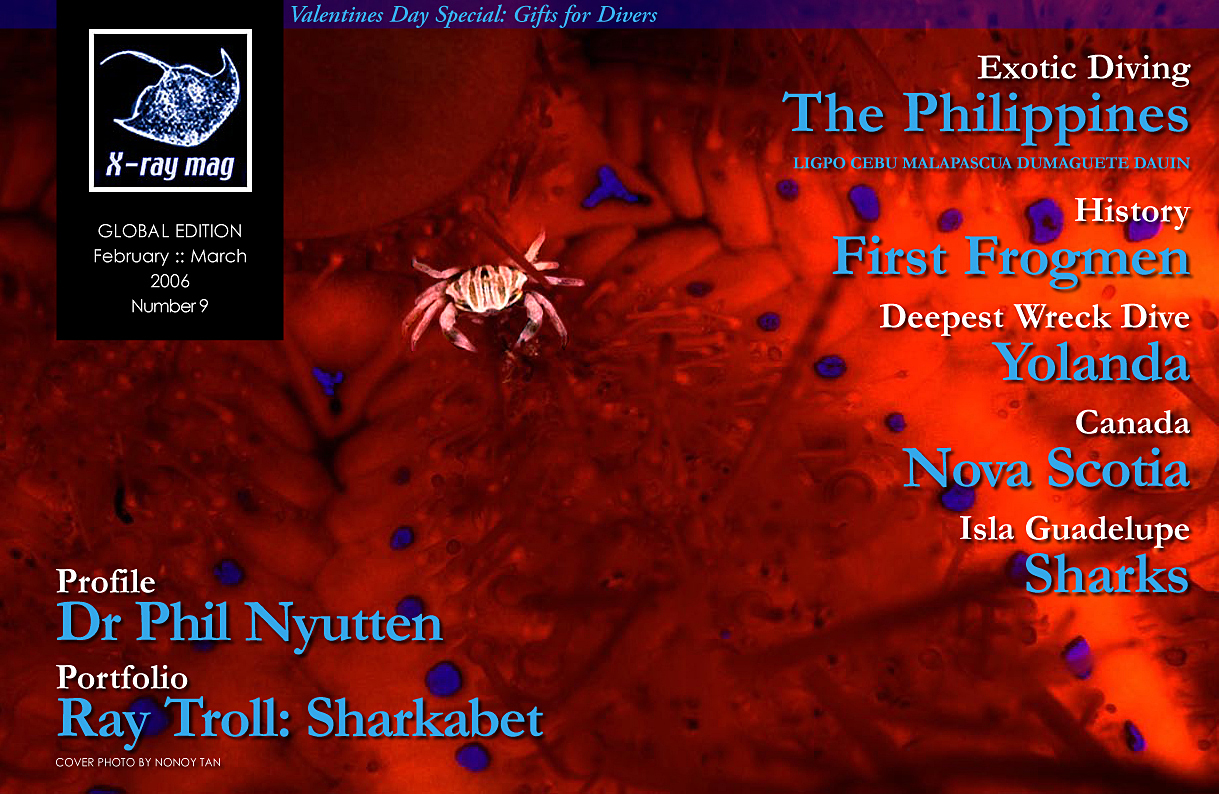

While this article was in production, Dr. Luigi Ferraro, one of the great Italian war heroes mentioned in this article and founder of Technisub passed away. First part of this article was published in X-Ray 7 as was a portrait of Technisub.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #9

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #9

- Log in to post comments