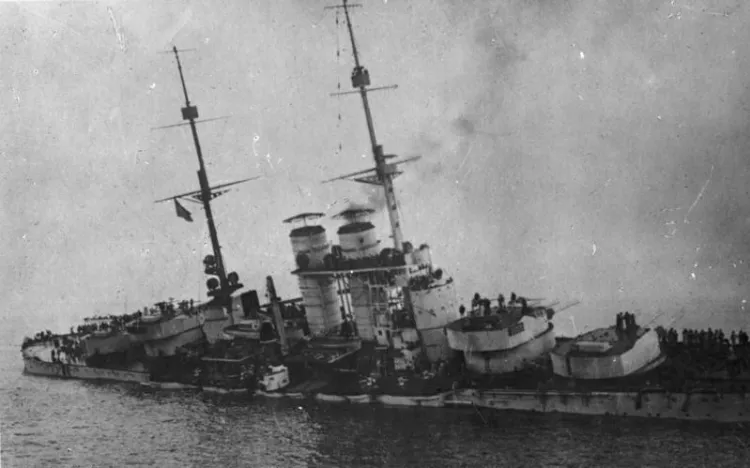

During WWI, the mighty warship from the Austrian-Hungarian navy was attacked at an unexpected moment. The brave crew of two Italian torpedo boats did not falter and the Szent István was struck twice with deadly force.

Contributed by

Factfile

Having dived over 400 wrecks, Vic Verlinden is an avid, pioneering wreck diver, award-winning underwater photographer and dive guide from Belgium.

His work has been published in dive magazines and technical diving publications in the United States, Russia, France, Germany, Belgium, United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

He is the organiser of tekDive-Europe technical dive show. See: tekdive-europe.com.

SMS Svent Istvan:

Dreadnought class of the Austrian-Hungarian navy.

Named after Hungary's first Christian king, Saint Stephen I.

Year built: 1914, by Ganz & Company Danubius Shipyard (in Fiume, now Rijeka)

Tonnage: 20,000 tons

Length: 152m

Beam: 28 m

Complement: 1094

Propulsion: 2 propellers

Speed: 20 knots

Armament:

4 x 12-inch (30cm) guns

12 x 5.9-inch (15cm) guns

12 x 2.8-inch (7cm) guns

3 x 66 mm AA guns

4 x 533mm torpedoe

It was a quiet night on 9 June 1918 when the two sister ships SMS Szent István and Tegettoff left the port of Pula (now Croatia) and set a course for Dubrovnik.

Both ships’ crews did not have much fear of being attacked by the Italian navy as they were accompanied by a destroyer and six torpedo boats. The Szent István was still a new ship of 20,000 tons, and up until now, had only used her gigantic 12-inch (30cm) cannons during gunnery practice.

The ship was named after the first Catholic king, Saint Stephen (in Croatian: Szent István). The initial plan was for both ships to have a rendezvous with the other units of the fleet and carry out an attack on the allied sea blockade near Brindisi. The captain and his officers were conducting a final preparatory meeting in the admiral’s cabin on the rear deck. He was issuing the final instructions while the watchkeepers were getting ready. It was a clear night and the lookouts had nothing to report; not one member of the more-than-thousand-strong crew suspected all hell was about to break lose.

Bold and courageous attack

It was just barely nighttime when the Italian corvette’s captain, Luigi Rizzo, gave the command to return to base. The torpedo boats MAS15 and MAS21 of the Italian navy had experienced a rough night, without much action, and were in a hurry to enter port.

As it was a clear night, they suddenly noticed smoke plumes on the distant horizon. It could only be an enemy ship in these waters. Captain Rizzo gave orders to his captains Gori and Aonzo to sail straight for the smoke plumes. Even though it was a long distance to sail, both torpedo boats succeeded in breaking through the cordon of escorting vessels and commenced the attack.

When they were in range of the two large battleships, Captain Rizzo decided to let the MAS21 initiate the attack against the Tegettoff. The torpedoes fired by the MAS21 missed the battleship. At the same time, the MAS15 set a course towards the Szent István and fired two torpedoes at her. Both torpedoes hit her in the flank, by way of the boilers. The rear boiler rooms immediately started to flood, giving the ship a 10-degree list to starboard.

Immediately, the captain of the Szent István gave the order to turn the heavy guns to port, as a way to counter the listing. However, more and more water poured into the boiler rooms, resulting in a loss of both power and pumping capacity. At 6:05 in the morning, the Szent István capsized and sank close to the Island of Premuda. The demise of the battleship was filmed by an officer of the Tegettoff and is the only film ever made during the First World War of the sinking of a warship. In this disaster, 89 crew members lost their lives.

Dive expedition to a protected war grave

The Szent István was discovered by the Yugoslavian navy in the 1970s and is now a protected wreck. You can only dive the wreck site with special permission. It took my Croatian friend Drazen Goricki a long time to get all the needed permissions. In the end, they were provided by the ministry of culture and the underwater archaeology department.

Many years had passed since the last time permission had been granted to a group to dive the wreck. Our team consisted of divers from five different countries, but divers from a special diving unit of the local police force and the Croatian navy would also be joining us.

Our home port during the expedition was the base of the special police diving unit in Mali Lošinj. We would be using their fast boat to go out to the wreck, which was 20 miles away from the base. At this base, it was also possible to get trimix and prepare our rebreathers.

This expedition was assisted by underwater archaeologist Igor Miholjek of the Croatian Conservation Institute. He was responsible for the retrieval and conservation of artefacts of the wreck. Igor was also an experienced trimix diver. It was also an intent during expedition to take as many film and photo images as possible, in and around the wreckage.

First reconnaissance with obstacles

It is not often you get the opportunity to dive a wreck that has been closed off to diving activities. Therefore, I wanted to prepare myself and subjected my equipment to a thorough check before leaving for Croatia. Even my camera was tested in every detail.

Preceding the first dive, the dive plan was discussed during the briefing and dive expedition members were divided into teams. My buddy was Phillipe Alfarei from Austria. Shortly before the dive, I tested my camera and noticed my flash was not working. I decided to take pictures with my video light instead.

During the descent to the wreck, it became apparent the visibility was no more than six metres. The downline was connected to one of the two large propellers and just beside these lay the rudders which were clearly visible.

After shooting some pictures, we descended farther towards the bottom and found an opening where we could swim underneath the wreck. The space where we were swimming was fairly large, and we found several leather shoes amongst the rubbish on the seafloor.

In the distance, some 15 metres ahead, we could recognise the large cannons, and there was an opening that led out of the wreck. The barrels of the 30cm guns were gigantic and gave a good sense of the scale of this enormous wreck. However, at a depth of 66m, time flies, so we had to swim back to the downline to start our ascent and a long decompression.

Admiral’s bathroom

During the following dives, Drazen found a passage to the admiral’s cabin. Here, several beautiful bronze lights with cut glass were retrieved for conservation, as was the telephone with which the orders were given to the bridge, found during one of the explorations deep into the wreck. It is obvious that, at 66 metres’ depth, these explorations were not without danger—more so, as the wreck was inverted on the seabed.

Close to the admiral’s cabin was also his bathroom, with a clearly recognisable bathtub. There was also some silver cutlery and porcelain retrieved from the various cabins.

During one of my dives, I discovered one of the large searchlights mounted on the mast, now partially hidden in the sand. Closer to the bow was the ammunition room, which was also filmed and photographed.

During the whole expedition, the weather was exceptional, with not much wind. More than 70 dives were made, and in the following months, all the recovered artefacts would be conserved and catalogued. Once this is done, the artefacts will be exhibited in a museum. ■