The entrance of the Sra Keow cave, north of Krabi, Thailand, is dark and quiet. All the local kids who use the pond as a playground are now back home for dinner. The only three people still there, closely watching the motionless pond, trying to see any bubble or glow that could reach the surface now start to worry. The divers were supposed to complete their dive within four and a half hours...

Still nothing after six long hours.

Contributed by

The entrance of the Sra Keow cave, north of Krabi, Thailand, is dark and quiet. All the local kids who use the pond as a playground are now back home for dinner. The only three people still there, closely watching the motionless pond, trying to see any bubble or glow that could reach the surface now start to worry. The divers were supposed to complete their dive within four and a half hours...

Still nothing after six long hours.

A few minutes later, one of the divers finally surfaces. He lays there for some extra minutes, breathing pure oxygen and resting, giving to his body the time to adapt to the surrounding pressure. Almost exactly two hours later, the second diver appears in the complete darkness. They have a lot in common: they look exhausted and cold, they wear black equipment and mixed-gas rebreathers—and they just came back from the deepest cave dive in Asia.

Just a crazy idea

A few months earlier the same divers had come to this site to conduct a first exploration into what is supposedly the deepest cave system in Thailand. Two entrances are connected together as the gateway to a giant kingdom with crystal clear water, providing easy access. Mike Gadd and Cedric Verdier, thanks once more to the precious support of Bruce Konefe in sorting out their logistics, then went deeper than any other diver in this cave: laying out a line in one of the passages going down to 150 m (490 feet).

The main passage is huge, and it was impossible to see the bottom of the cave. This first expedition was such a success that they all decided to come back as soon as possible, which, however, due to the team member’s other occupations would take another four months. Meanwhile, the abyss just had to wait.

Just a crazy plan

Cedric lives in Thailand and Mike in Singapore. Both wanting to going back to explore the cave down to the 200m level, they soon found themselves communicating almost daily on the matter, finding themselves face to face with a daunting technological and physiological challenge. As for the equipment side of matters, Mike dives with an Ouroboros and Cedric with a Megalodon CCR.

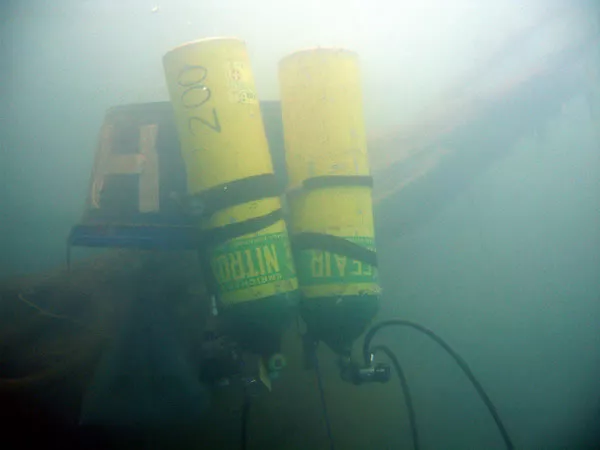

Even if both units are extremely reliable and have a good reputation in the deep diving community, nobody has ever tested them to these depths. A few minor changes were necessary, mainly on the Megalodon, in order to carry out these dives with an acceptable level of safety. The handsets and the battery compartments were filled with mineral oil to withstand the 21 ATA of ambient pressure and all air-filled pressure gauges were removed.

Every single piece of equipment was thoroughly inspected and the divers meticulously read every user manual of all their gear (canister light, back-up lights, computers and depth gauge) to learn more about the crushing depth of each. Nevertheless, the notion of having some piece of gear imploding at depth never really left their minds.

Which dive plan?

Planning a dive to 200m (660ft) is clearly different than planning a “normal” trimix dive—if there is ever such a thing. The divers had long discussions about the right mix, the right setpoint and the right decompression procedures. To the bystander, the dive plans that both divers exchanged must have sounded like an elaborate code concocted by a secret agent on magic mushrooms.

Eventually, Mike and Cedric finally agreed to use only one diluent all the way to the surface, to limit their setpoint on the bottom while slightly increasing it during the ascent. The deco obligation would be longer than when using multiple diluents, but the off-gassing process would be smoother. They also agreed on “trusting” the VPM-B/E algorithm implemented in V-Planner to safely bring them to the surface.

Making it back?

Diving deep is one thing. Also coming back alive is another. It is, therefore, of paramount importance that thorough contingency plans are made for every conceivable emergency or unexpected event. Both divers spent an interesting evening in a pizzeria in Krabi, running over and planning for every “What if…” they could imagine. At the end of it, they opted for a comfortable safety margin by staging multiple tanks in the cave in the case one of them had to ‘bail out’ on open circuit. That, however, meant more tanks than a body builder could safely lift and a real challenge in keeping the whole set up fairly streamlined.

Dealing with heat loss

Extremely long exposures, even in quite warm waters (around 26°C at the surface), are also a concern. A dry suit is clearly a must, even if it means a difficult and very hot gear-up session in the tropics. A proper hydration schedule is also required (as is the P-valve). It was decided to set up two very basic habitats, one for emergency at 12m (40ft) in case of convulsion (a.k.a throwing up!) and one at 6m (20ft) for comfort (to drink and eat some junk food). The divers couldn’t help being concerned whether the local kids were able to free dive to the habitat and have a feast on the candy bars placed there for the returning divers.

Just a crazy expedition

Diving in a pond surrounded by hysterical kids and impressive elephants is something that most divers will never experience. But gearing up with state-of-the-art rebreathers, full face mask and astronaut suits with a lot of sunburnt tourists and puzzled locals is not the best part of the dive. It is quite difficult to focus on a rebreather check-list when people come to ask you one of the most stupid questions imaginable - “You’re going diving?”—as if you were considering going for a trek in the jungle with more than 80 kg of tanks on your back and a suit that makes you sweat your body weight every minute.

The equipment piled up all around the pond was very impressive, with the equipment for the bottom divers, all the stage tanks and the big twin sets of the support divers. The local people were also quite surprised to see both divers installing the two habitats (barely more than two blue buckets) which were simply named Ritz and Hilton. Everything would have been perfect if not for the rain. Unfortunately, the masses of water coming out of the clouds soon displaced water in the pond and the visibility quickly started to decrease until it was close to zero.

This didn’t make the dive any easier: the entrance of the cave is a restriction and following the guideline in a low viz would certainly slow down the descent. But in a very international team (American, British, German, Thai and French), there is always somebody to keep the spirits high.

Just a crazy dive

On the “big day”, everyone is focused. Mike is going through his extensive – and quite long – Ouroboros check-list, Cedric listens to his MP3 player while checking his equipment, and the support divers are in the middle, trying to help them without disturbing them. After a long process of gearing up and sweating at the surface—and a few minutes to relax at the surface—both divers finally submerge along the descent line that Bruce installed earlier.

It will take 6 minutes to reach 60m (197ft). Then a long descent will follow to reach the end of the line at 150m (490ft). After a few seconds of hesitation and rest, a new line is laid and the divers continue the descent. The cave is massive and the water is very clear compared to the surface. Even with powerful lights, it is not possible to clearly see the opposite wall. The walls are vertical and as smooth as the shaved legs of a fashion model. There seemed to be nowhere where the divers could wrap the line around a rock or formation. Mike finally finds a place to tie off the line, cut it and recover his expensive reel. Cedric is slightly below him, looking at the impressive environment. At 200m (660ft), he still can’t see the bottom, which is at least a further 20m below.

At 200m

Both divers are relieved that none of the equipment has imploded and that both rebreathers have performed flawlessly. The work of breathing is still good, and there is no sign of hypercapnia, even with the standard axial canister in the Megalodon. After a few minutes exploring the cave, it’s already time to start the ascent. The first stop is planned at 135m (443 ft)—just the beginning of a very long ascent.

Surprises

The funny thing about dive planning is that even if you plan for the worst case scenario, you can still be surprised. True to this principle, the ascent turned out to be everything but boring. First, even after bringing plentiful amounts of gas for suit and wing inflation, both divers were heavy on the bottom and Cedric ran out of gas for his wing and had to switch tanks and reconnect his low pressure Inflator—something you don’t like to do at 200m in mid-water, kicking hard to maintain your depth.

Secondly, all the computers used gave massive decompression obligations (especially the VR3 VPM) with long deep stops and overall hang time over six hours. Even if you plan your decompression very carefully, your common sense is always reluctant to “bend” your computer and fully trust your tables. Therefore, both divers were late compared to their decompression schedules, and the support divers were surprised and concerned not to find them around the expected depth.

... and there is more

Next, with such a low visibility, a line trap became the opportunity to understand the true meaning of streamlining one’s equipment. Cedric and Mike both cursed (respectively in French and in English) when they couldn’t find a way to follow the line with all their sling tanks and had to descend a little bit to find the proper passage. Then the Ritz habitat decided to sink and become entangled in the main line. Cedric was quite surprised to bump his head into a plastic bag full of fruit juice.

Going on to the next unforeseen event, some annoying shrimps came to the decompression stops to find out whether the soft skin of mixed-gas divers could supplement their regular diet. Just so you know, it’s extremely painful when these lovely creatures bite your face. Because of the extremely low visibility, reading the gauges was also very difficult. Some mistakes in the run time were made, and the ascent was even more delayed. On a lighter note, the anti-dehydration plan was very effective and both divers exchanged their points of view. Cedric was happy to see his bladder still active at 200m and Mike enjoyed letting it go every 10 minutes.

Both divers spent a very long time at their shallowest stops, reading, sleeping or swimming around. Having drifted from the decompression station (a submerged tree trunk conveniently located at 6 and 4.5m), Mike was surprised to find a solid rock over his head when he started his final ascent to the surface. He had to look for the exit for quite a long time, while avoiding a descent (no diluent left).

8:30pm - and back!

Both divers are back at the surface. According to the support divers, Cedric is blue and Mike looks rather tired. They look at each other without really believe it.

- The deepest dive ever done with an Ouroboros (191m/ 626 ft).

- The deepest dive ever done with a Megalodon (201m/ 663 ft).

- The deepest cave dive in Asia.

No mechanical problems, no CO2 hit, no signs or symptoms of DCS. Quite an accomplishment.

They slowly pack their gear, helped by the support divers. Everything is dark and quiet and the lights from the car hardly help to gather all the equipment without losing anything. Anyway, tomorrow will be a clean-up dive. There are so many unused bail-out tanks to retrieve. Someone jokes about using them for a deeper dive during the next expedition. Someone else jokes about using Heliox instead of Trimix.

But jokes are all there is to it now. ■