Two of the resident orca families from Puget sound —L and K pods—have been seen in recent years feeding off the California coast in the winter. That was unheard of before early this decade, leading scientists to speculate they are driven to swim hundreds of miles just to meet their minimum nutritional requirements. Showing signs of starvation as salmon runs faltered up and down the west coast, Puget Sound’s orca population lost seven of its number over the past year, bringing the population to just 83, scientists reported.

Experts believe the population of the J, K and L pods that frequent the San Juan Islands and Puget Sound probably originally numbered between 100 and 200.

“Eighty-three is low. The real number that’s of concern is that we only have about a dozen reproductive females,” said Ken Balcomb, founder of the Center for Whale Research on San Juan Island.

It is conceivable that one or more of the missing orcas might have wandered off on its own and is still alive. But orca scientists doubt that because it’s only been documented happening two times in history. Other than that, orcas always have stayed with their families. Researchers are pretty sure all seven are dead—and it makes sense, because supplies of their favorite food were so low.

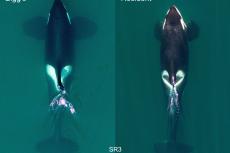

Two recently deceased females showed signs characteristic of starvation—particularly a depression behind her skull where blubber should be. The condition is known as “peanut head.”

Chinook salmon

The development marks the biggest reduction in the orca population since a series of bad chinook salmon seasons in the 1990s battered the killer whales’ numbers.

Revealing the degree to which the orcas are interrelated to a far-flung marine ecosystem,the collapse of California’s Sacramento Valley chinook run seems likely to be partly to blame for declining killer whale numbers, said Balcomb. Studies have shown that orcas have a strong preference for chinook salmon, pursuing other prey only when their primary food source is scarce. That makes scientists wonder whether there is something particular about chinook salmon that the orcas need to thrive. “We know that in bad chinook years the orca population declines,” Balcomb said. “It’s like if you don’t feed your pets— they don’t survive. They start losing body fat.”

Chemicals to blame?

Is direct starvation the only reason? There might be something else going on too. In recent years, scientists have noted in the orcas extremely high levels of chemicals known to interfere with reproduction, finding food and other functions.

Like humans, orcas begin to burn their fat supplies in times of low food supplies. And the fat is where PCBs and other long-lived industrial chemicals are stored.

Do these chemicals, once freed, have some other effects? Studies on dolphins and Puget Sound harbor seals showed the chemicals caused reproductive problems and made the seals more likely to get sick. Dolphins and seals are mammals, too.

Scientists are trying to assess the health of the orcas by collecting their waste and what’s in the breath they exhale through their blowholes.

What Hormones Reveal

A team from University of Washington measured the levels of two metabolic hormones in fecal samples from Puget Sound killer whales. The results confirmed that the orcas were under “nutritional stress” this year.

Graduate student Katherine Ayres said levels of thyroid hormone appeared to be low this year when compared with last year—a year when killer whale deaths were low. These hormones control a mammal’s metabolism and increase or decrease over time, causing less energy to be expended when food supplies are low. Consuming less food causes the thyroid to slow the metabolism and conserve fat reserves, which leads to rapid weight gain when food is restored. It appears the Puget Sound orcas went on an unintended diet this past summer, Ayres said.

Other interesting clues came from the levels of cortisone which is another hormone. Cortisol is a rapidly produced in response to mental or emotional stress. Normally cortisol levels are lowest during July and August when chinook salmon are most abundant and whales are under the least stress.

Because cortisol is produced more rapidly during stressful conditions, Ayres also investigated whether hormone “spikes” could be linked to whale-watching boat. Preliminary findings indicated that cortisol levels were higher after a weekend, when more boats are around, than during the week. “It’s premature to talk about the boat effect,” she said. “The bigger one we’re seeing is the nutritional one.”

Ayres also is working on a test to measure the levels of toxic chemicals in feces. Because a shortage of food tends to metabolize fat stores in whales, it is likely that toxic chemicals stored in fat would be released when thyroid levels are low. Toxic chemicals are believed to affect the whales’ immune systems and increase their risk of disease.

Bacteria or fungi?

Meanwhile other research by biologist, David Bain, and veterinarian, Pete Schroeder, studying droplets emitted from orca blow holes have found drug-resistant bacteria. Puget Sound’s orcas collectively harbour more than a dozen different kinds of antibiotic-resistant bacteria—as well as other bacteria known to kill animals that are in a weakened condition. Because some bacteria show resistance to antibiotics, it is likely that they are coming from human sources, possibly stormwater or improperly treated sewage, says Schroeder.

Another concern is that a disease could get into animals on land and spread to Puget Sound. “We don’t have an effective barrier to keep it out of the marine environment,” Bain said. “It is possible that someone could bring a disease from another continent and expose the whales, causing a significant decline in their population.”

For example, a fungus called cryptococcus gattii has been implicated in the deaths of dozens of harbor porpoises in the northwest, he said. That same fungus has resulted in the deaths of numerous pets and serious illness for humans. Some researchers believe the fungus was brought to British Columbia in a eucalyptus tree from Australia, where the fungus is native.

Spores may have washed into stormwater flowing into the Georgia Basin, which connects with Puget Sound.

Noise perhaps?

A new study suggest that orcas use their natural sonar to find their favorite fish from a distance. Like other many other marine mammals orcas emit high-frequency clicks that are reflected back when the sound waves strike an object. The animals use sonar information to navigate, hunt, and communicate in murky waters. But orcas may have taken their use of sonar to a level of sophistication where it enables them to select specific types of prey.

Previous research had revealed that some killer whales off the coasts of British Columbia and Washington State have an uncanny ability for finding chinook salmon, even in months when chinook are vastly outnumbered by other salmon species such as coho and sockeye.

“Chinook salmon have a higher concentration of fat than other species of salmon and apparently killer whales like that,” said study co-author Whitlow Au, a bio-acoustician at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. Au and his team simulated echolocation clicks resembling those of wild killer whales to measure the echoes produced when the sound waves bounced off the bodies of three kinds of salmon. The team found that each salmon species has a unique echo pattern based on the different sizes and shapes of their swim bladders.

The air-filled sacs show up clearly in the echo images because they have a different density than the surrounding flesh and water. The swim bladder “is responsible for at least 90 percent of the sound energy that is reflected from the fish,” said study team member John Horne of the University of Washington. “Think of it as a hard wall.”

Although Chinooks on average are larger than the other two salmon species, individual sizes overlap between the three groups, so the team doesn’t think orcas are selecting prey solely based on body size. ■